By Adam Ellis – @AdamEllis22

BEFORE the time of modern football when billionaire club owners were a distant speck on the sport’s mainstream, in the hazy jungles of Peru the land’s feral foundations lay bear a spring for hyper-wealth. Riches so great they were unmanageable.

Coca leaves were more abundant in the western perimeter of the Amazonian rainforest than anywhere else in the world, but were yet to be harnessed by criminal elements on a pan-American scale.

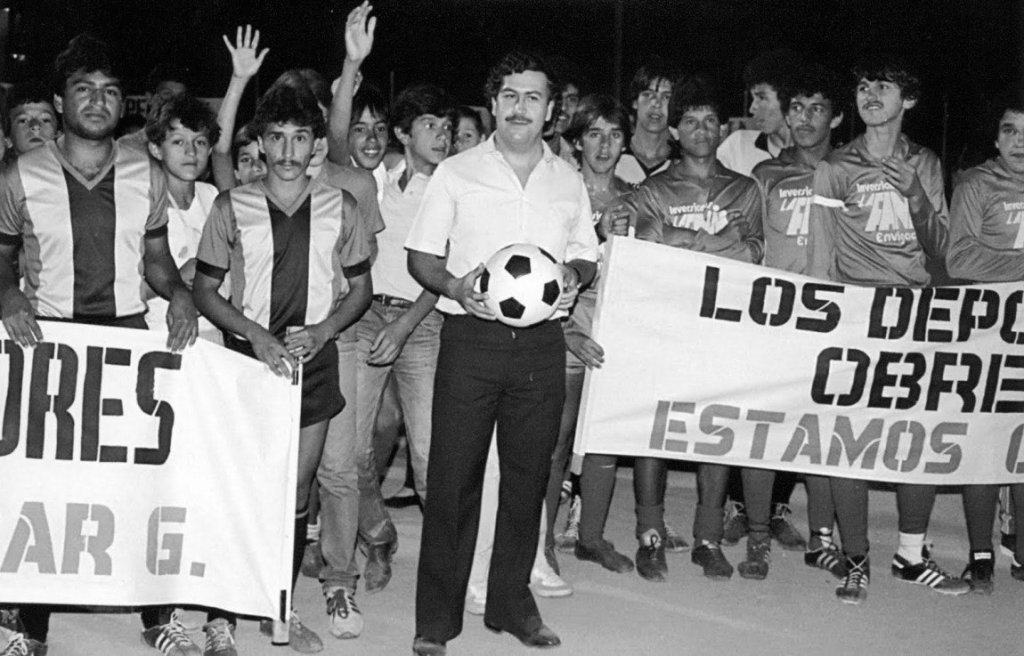

Pablo Escobar, the man who experienced being sent home from school as a young boy for having no shoes, became the kingpin.

As an adolescent, he would visit his uncle’s workplace – the local cemetery – to collect headstones which had long been abandoned by the kin of past generations, buy them, scrub them clean, and turn them over to grieving local citizens for a new name to be marked.

The young man would go on to study political science at Universidad de Antioquia, where charisma and public speaking skills matured to forge his ultimate goal of becoming the president.

He was undeterred in his pursuit of his life ambition: to lead his homeland, a nation rife with political fractures and destabilized by militant warfare.

In 1982, security fears were running so deep that US president Ronald Reagan afforded himself five hours with the then Colombian president Belisario Betancur at a time when Latin America threatened to spiral into a left-wing matrix.

Castro, the El Salvadoran Civil War, and communist factions had all contributed to tense relations between Washington and the Americas, a preoccupation which allowed Pablo Escobar to establish his cocaine production and trafficking system while portraying an identity as a successful ‘real estate developer’.

Money flowed into Escobar’s home city of Medellin as if through an oil pipeline. The merge between metropolitan development and the city’s mountains typical to the Antioquia region left the cartel with the option of fight or flight should danger loom.

Despite drug busts in Miami and Los Angeles which made grandiose headlines in the States, Escobar was more troubled by running out of Caletas (storage spaces created between the walls of a house to stash money) and found himself in increasing need of sourcing other means to hide his millions.

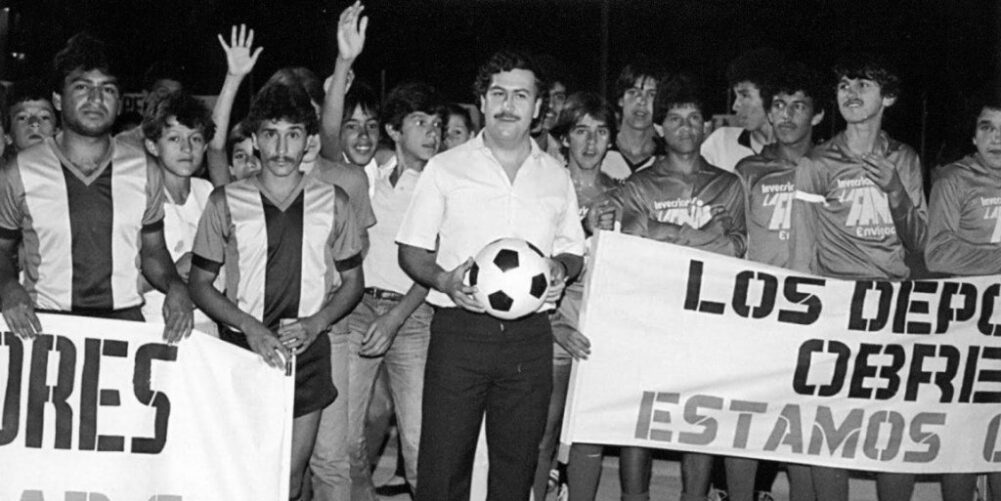

As the Netflix series Narcos has alluded to, Escobar’s favourite pastime was football; playing, watching, betting, and, to his own benefit, investing.

For Pablo, TV rights deals, player transfers, and gate receipts all represented a crooked way to keep his money in check and a sheening halo firmly on his head to keep the authorities at bay.

Year-after-year, revenue figures could be injected with drug money that would go through the cycle of his comfortably-paid team of accountants, who would return the money back into his pocket with a bonus.

Medellin is a city of two teams: Deportivo Independiente Medellin – the club Pablo’s son claims his father supported – and Atletico Nacional.

His opting to plough dirty money in to Nacional may be down to the majority of people in Medellin wearing the green colours of Los Verdolagas, which mirror the hills bordering the city.

As opposed to Independiente who had failed to win Primera A since 1957, and whose red jerseys would reflect the colour of the streets as the drug war entered the 1990s.

By 1987, Escobar had been outed by Forbes Magazine as the ‘chief paisa’ behind Colombia’s illegal cocaine distribution; the magazine placed on the record that his fortune amounted to a minimum of $3bn.

For all the material luxuries on offer to his riches, Escobar had the one thing a person from any walk of life can rely on: feeling a belonging to a club.

He developed a close friendship with pioneering goalkeeper Rene Higuita – arguably one of the first to conquer the ‘sweeper keeper’ role now anointed to Manuel Neuer.

Higuita was the rock which coach Francisco Maturana depended on, writing in 1990:

Jan Jongbloed, the Holland keeper in the 1974 World Cup, also operated as a sweeper. With a difference. The Dutchman came out just to boot the ball into the stands. Higuita can do much more.

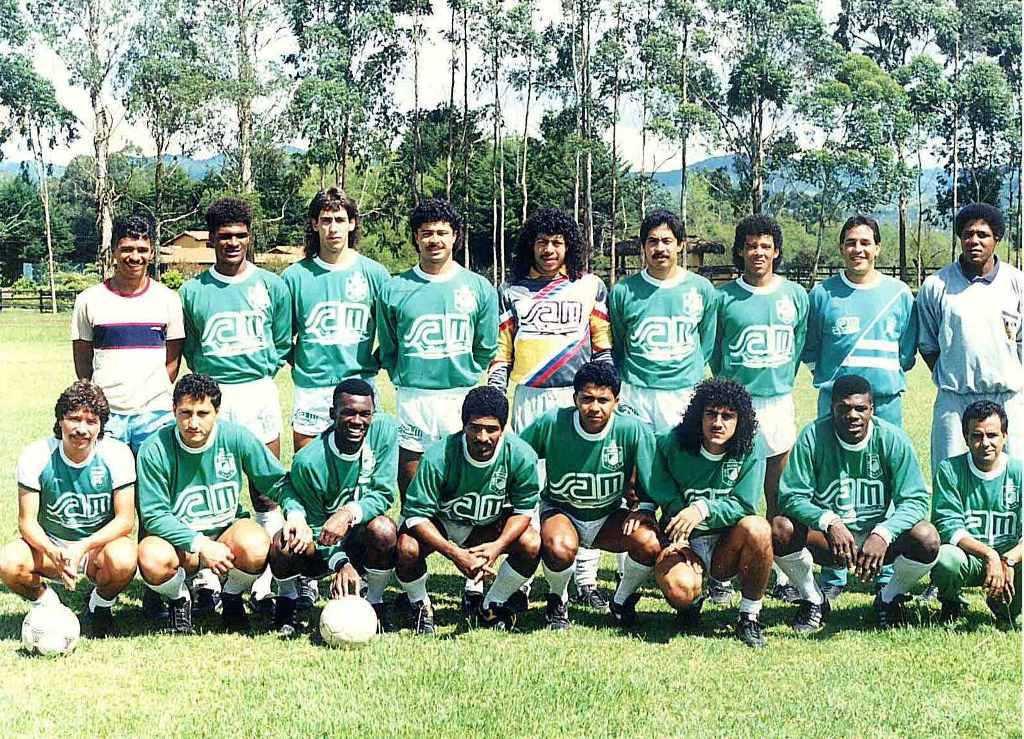

Andres Escobar, Leonel Alvarez and John Jairo Trellez formed the other components to the spine of Nacional’s team.

Maturana invoked a positive mental attitude to a core of technical players who could be retained by Nacional through Escobar’s money. As Nacional’s stock rose throughout the Americas so did Maturana’s; by 1987 he was contacted by the Colombia Football Federation to coach their youth teams and would quickly fast-track his way through to the national team’s top job.

Things were going well. Maturana, a noticeable grey-suited figure in the home dugout at Atanasio Girardot Stadium, was archetypal in being a manager of his team’s psychology. An unerring loyalty was built into the squad’s DNA along with a ruthless self-belief.

This was demonstrated by Nacional’s 6-0 victory in the semi-final second leg of South America’s Copa Libertadores. Uruguayan club Danubio left nothing to separate the two sides in the first meeting, playing out a 0-0 draw. But with an emphatic victory that showed no signs of nerves, Nacional were into their first ever final of the competition equivalent to Europe’s Champions League.

Their opponents Olimpia had experienced national adulation back in 1979 to become the first club from Paraguay to win the trophy, and now Nacional were seeking to do the same for a divided Colombia.

There was a feeling of destiny, something that often lends itself to the dramatic… cue a penalty shoot-out.

All square on aggregate at 2-2, the first five penalties provided no winner with Nacional midfielder Alexis Garcia unable to capitalise on Ever Almeida’s woeful attempt.

Sudden death put our own Three Lions’ penalty record to shame, with six penalties missed one after the other until Leonel Alvarez sparked a pitch invasion by ending the passing of the buck.

The game won 5-4 on penalties, Nacional lifted the trophy. A team playing in a country savaged by war and having its sovereignty disputed by the US government provided a brief distraction for the green side of Medellin and every Colombian neutral.

But who deserved the credit for Colombia finally earning a star next to their name in the 29th year of Copa Libertadores contests?

The purists will vouch for Maturana, a man backed by his future endeavors with the national team, heading into the 1994 World Cup as the favoured dark horse off the back of a 34-match unbeaten run.

Someone inspired by the philosophies of Argentina coach Cesar Luis Menotti, the chain-smoking tactician who said, “To be a footballer means being a privileged interpreter of the feelings and dreams of thousands of people.”

Maturana was a coach capable of making a demand to his players without becoming the aggressor. Charisma was a tool he had and he knew how to use it.

The realists will argue Escobar’s influx of money allowed Colombia’s game to grow while the leagues of other Latin American nations had to contend with Italy stealing their honey. For this to happen, Escobar needed an in into Nacional. How he did this has yet to be verified. But someone at Nacional did pay the price even before Escobar had garnered worldwide fame for his notoriety.

In a stark warning to the country’s drug cartels, Colombian justice minister Enrique Parejo reacted to the murders of a Supreme Court justice, 20 judges and two newspaper editors by issuing the extradition of 12 nationals to the US.

Owner of Nacional, Hernan Botero Moreno, who bankrolled the club through his family’s successful hotel business, was one of the 12 fed to the crocs of the US judicial system.

Made fiercer by the stringent American drug laws created by Richard Nixon in the 70s and hardened by Ronald Reagan in the 80s, Botero faced considerable time in prison.

Charged with laundering at least $55m through a bank in Florida on behalf of the Medellin cartel, the 52-year-old was jailed for 20 years in a maximum-security prison by a judge in Washington.

The story of Botero is the story of Colombia in the 20th century. Humble beginnings quickly divided into something sinister.

The death of Pablo Escobar gave hope for peace in 1993. But upon Botero’s release from prison in 2002, the country was still confronting a left-wing militancy which the government had been incapable of neutralising for 50 years and one in two of the population lived below the poverty line.

Colombia continues to have its issues but football, as it often does, has provided a distraction. The national team ended 2016 third in the FIFA world rankings.

As for Nacional, they matched their feat of 1989 by winning the Copa Libertadores for the second time in their history.

A moment of jubilation missed by Botero, who died a free man 27 days prior to Los Verdolagas’ taste of silverware.

Tellingly, in a country that has retained its place as the world number one exporter of cocaine, Medellin’s star product Marlos Moreno was sold for £4.75m to Manchester City this summer. The champions of South America unable to safeguard their talent against the riches of Europe – welcome to the status quo, Colombia.

*This article originally featured in Late Tackle, with the next edition available on April 20th.